( from "Three Men in a Boat", by Jerome K. Jerome)

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/308/308-h/308-h.htm

I remember a friend of mine, buying a couple of cheeses at

Liverpool. Splendid cheeses they were, ripe and mellow, and

with a two hundred horse-power scent about them that might have

been warranted to carry three miles, and knock a man over at two

hundred yards. I was in Liverpool at the time, and my

friend said that if I didn’t mind he would get me to take

them back with me to London, as he should not be coming up for a

day or two himself, and he did not think the cheeses ought to be

kept much longer.

“Oh, with pleasure, dear boy,” I replied,

“with pleasure.”

I called for the cheeses, and took them away in a cab.

It was a ramshackle affair, dragged along by a knock-kneed,

broken-winded somnambulist, which his owner, in a moment of

enthusiasm, during conversation, referred to as a horse. I

put the cheeses on the top, and we started off at a shamble that

would have done credit to the swiftest steam-roller ever built,

and all went merry as a funeral bell, until we turned the

corner. There, the wind carried a whiff from the cheeses

full on to our steed. It woke him up, and, with a snort of

terror, he dashed off at three miles an hour. The wind

still blew in his direction, and before we reached the end of the

street he was laying himself out at the rate of nearly four miles

an hour, leaving the cripples and stout old ladies simply

nowhere.

It took two porters as well as the driver to hold him in at

the station; and I do not think they would have done it, even

then, had not one of the men had the presence of mind to put a

handkerchief over his nose, and to light a bit of brown

paper.

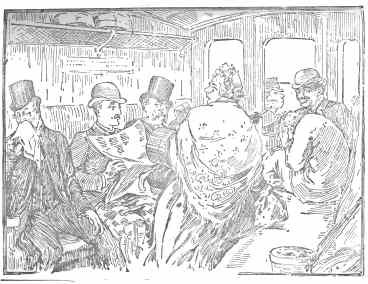

I took my ticket, and marched proudly up the platform, with my

cheeses, the people falling back respectfully on either

side. The train was crowded, and I had to get into a

carriage where there were already seven other people. One

crusty old gentleman objected, but I got in, notwithstanding;

and, putting my cheeses upon the rack, squeezed down with a

pleasant smile, and said it was a warm day.

A few moments passed, and then the old gentleman began to

fidget.

“Very close in here,” he said.

“Quite oppressive,” said the man next him.

And then they both began sniffing, and, at the third sniff,

they caught it right on the chest, and rose up without another

word and went out. And then a stout lady got up, and said

it was disgraceful that a respectable married woman should be

harried about in this way, and gathered up a bag and eight

parcels and went. The remaining four passengers sat on for

a while, until a solemn-looking man in the corner, who, from his

dress and general appearance, seemed to belong to the undertaker

class, said it put him in mind of dead baby; and the other three

passengers tried to get out of the door at the same time, and

hurt themselves.

I smiled at the black gentleman, and said I thought we were

going to have the carriage to ourselves; and he laughed

pleasantly, and said that some people made such a fuss over a

little thing. But even he grew strangely depressed after we

had started, and so, when we reached Crewe, I asked him to come

and have a drink. He accepted, and we forced our way into

the buffet, where we yelled, and stamped, and waved our umbrellas

for a quarter of an hour; and then a young lady came, and asked

us if we wanted anything.

“What’s yours?” I said, turning to my

friend.

“I’ll have half-a-crown’s worth of brandy,

neat, if you please, miss,” he responded.

And he went off quietly after he had drunk it and got into

another carriage, which I thought mean.

From Crewe I had the compartment to myself, though the train

was crowded. As we drew up at the different stations, the

people, seeing my empty carriage, would rush for it.

“Here y’ are, Maria; come along, plenty of

room.” “All right, Tom; we’ll get in

here,” they would shout. And they would run along,

carrying heavy bags, and fight round the door to get in

first. And one would open the door and mount the steps, and

stagger back into the arms of the man behind him; and they would

all come and have a sniff, and then droop off and squeeze into

other carriages, or pay the difference and go first.

From Euston, I took the cheeses down to my friend’s

house. When his wife came into the room she smelt round for

an instant. Then she said:

“What is it? Tell me the worst.”

I said:

“It’s cheeses. Tom bought them in Liverpool,

and asked me to bring them up with me.”

And I added that I hoped she understood that it had nothing to

do with me; and she said that she was sure of that, but that she

would speak to Tom about it when he came back.

My friend was detained in Liverpool longer than he expected;

and, three days later, as he hadn’t returned home, his wife

called on me. She said:

“What did Tom say about those cheeses?”

I replied that he had directed they were to be kept in a moist

place, and that nobody was to touch them.

She said:

“Nobody’s likely to touch them. Had he smelt

them?”

I thought he had, and added that he seemed greatly attached to

them.

“You think he would be upset,” she queried,

“if I gave a man a sovereign to take them away and bury

them?”

I answered that I thought he would never smile again.

An idea struck her. She said:

“Do you mind keeping them for him? Let me send

them round to you.”

“Madam,” I replied, “for myself I like the

smell of cheese, and the journey the other day with them from

Liverpool I shall ever look back upon as a happy ending to a

pleasant holiday. But, in this world, we must consider

others. The lady under whose roof I have the honour of

residing is a widow, and, for all I know, possibly an orphan

too. She has a strong, I may say an eloquent, objection to

being what she terms ‘put upon.’ The presence

of your husband’s cheeses in her house she would, I

instinctively feel, regard as a ‘put upon’; and it

shall never be said that I put upon the widow and the

orphan.”

“Very well, then,” said my friend’s wife,

rising, “all I have to say is, that I shall take the

children and go to an hotel until those cheeses are eaten.

I decline to live any longer in the same house with

them.”

She kept her word, leaving the place in charge of the

charwoman, who, when asked if she could stand the smell, replied,

“What smell?” and who, when taken close to the

cheeses and told to sniff hard, said she could detect a faint

odour of melons. It was argued from this that little injury

could result to the woman from the atmosphere, and she was

left.

The hotel bill came to fifteen guineas; and my friend, after

reckoning everything up, found that the cheeses had cost him

eight-and-sixpence a pound. He said he dearly loved a bit

of cheese, but it was beyond his means; so he determined to get

rid of them. He threw them into the canal; but had to fish

them out again, as the bargemen complained. They said it

made them feel quite faint. And, after that, he took them

one dark night and left them in the parish mortuary. But

the coroner discovered them, and made a fearful fuss.

He said it was a plot to deprive him of his living by waking

up the corpses.

My friend got rid of them, at last, by taking them down to a

sea-side town, and burying them on the beach. It gained the

place quite a reputation. Visitors said they had never

noticed before how strong the air was, and weak-chested and

consumptive people used to throng there for years afterwards.